Adults are often peripheral figures in teen horror. There may be some conflict when a characters’ parents don’t like the person they’re dating or won’t let them borrow the family car, and the teens may occasionally grumble about a boring class or a teacher assigning too much homework. But usually, adults are to be tolerated, circumnavigated, and talked to as little as possible (even when they actually might be able to help). But in R.L. Stine’s Fear Street books The Dare (1994) and Final Grade (1995), characters decide their teachers have pushed them too far and the only path forward is murder.

Just like with her blackmail horror classic I Know What You Did Last Summer (1973), Lois Duncan did it first, with Killing Mr. Griffin (1978), and a quick overview of Duncan’s book is essential in establishing the foundation that Stine builds upon with The Dare and Final Grade. Mr. Griffin is a tough English teacher and demands the best from his students, not willing to let them slide with subpar work or assignments turned in late. He has a zero tolerance policy for cheating and when student Mark Kinney gets busted for turning in a stolen paper for his essay assignment, he finds himself taking Mr. Griffin’s class again the next year, and not at all happy about it. Mark, his friend Jeff Garrett, and Jeff’s girlfriend Betsy Cline decide the best way to deal with Mr. Griffin making their lives miserable is to fake a kidnapping, blindfold him, and make him think they’re going to murder him. But since they’ve all three been in trouble with Mr. Griffin, they need a couple of patsies to help with their scheme, so they recruit class president David Ruggles and a shy girl named Susan McConnell.

Interestingly, while the later teen horror riffs on this theme privilege the teen characters’ perspectives, Duncan provides readers with insight into Brian Griffin’s personal life and motivations, including what drives him to hold the students to such a high standard. Mr. Griffin had previously been a college professor, but decided to make the change to teaching high school because he thought he could make more of a difference and have a positive impact on students’ lives. As he explained to his wife Kathy, the college students he worked with at the university were unprepared for higher education: “They’ve had twelve years without disciplined learning, and they don’t know how to apply themselves. They haven’t learned to study or to pace their work so that projects get completed on time. They fall asleep in lectures because they expect to be entertained, not educated” (55). While this isn’t a particularly generous view of his students and fails to take into account the diverse learning styles that may be coming into play, instead of just grumbling about it, Brian wants to make a change to help improve the situation. As a high school teacher, he tells Kathy, “I’d push each one into doing the best work of which he or she was capable. By the time they finished a class with me, my college prep students would be able to handle university work … [And] The others would graduate with a knowledge of what disciplined work is all about. That should stand them in good stead, no matter what they decide to do” (55-56). As a high school teacher, that’s how he leads his classes and interacts with his students, true to those values and priorities. He may be rigid and a bit short on empathy, but his intentions are good.

When the kidnapping plot kicks into action, things don’t quite go as planned—Betsy gets a speeding ticket while driving to meet the others, which blows a hole in their collective alibi, and while they are able to successfully kidnap Mr. Griffin and take him to a secluded spot in the wilderness, he doesn’t cave and beg for mercy, like they hoped. So they decide to leave him there, tied up and blindfolded, to think about the error of his ways, then come back and get him that night after the high school basketball game. Susan worries about Mr. Griffin, gets nervous, and talks David into going with her to untie their teacher, ready to face whatever consequences there may be, but when they get there, Mr. Griffin is dead. His death is the result of a pre-existing heart condition that he’s usually able to manage with prescription medication, but the kids took his pills when they tied him up and even if they hadn’t, he wouldn’t have been able to get to his medication with his hands tied. The teens’ intended “prank” evolves into a murder cover up with Mark directing everyone’s actions, as they bury Mr. Griffin’s body, take his car to the airport to make it look like he skipped town, and cook up a phony story about how Susan saw him leaving school that day with a mysterious woman.

When David and Susan advocate for coming clean—particularly after Mr. Griffin’s body is found and they see the tragic ramifications of their actions on Mr. Griffin’s pregnant widow—the depth of Mark’s danger becomes clear, as he kills David’s grandmother and tries to kill Susan, tying her up and setting her house on fire. Susan is saved, the truth comes out, and the teens must take responsibility for what they have done, though there are intricacies in that assignment of responsibility. Mark is clearly the ringleader and potentially a psychopath, according to Susan’s mom’s consultation with a psychologist, as she presents Susan with the definition of an “individual [who] is unique among pathological personalities in appearing, even on close examination, to be not only quite normal, but unusually intelligent and charming. He appears quite sincere and loyal and may perform brilliantly at any endeavor. He often has a tremendous charismatic power over others” (218-219). This shunts a good deal of the burden of responsibility onto Mark, who will be charged with the murders of Mr. Griffin and David’s grandmother, as well as his attempt to murder Susan. Mark’s alleged psychopathy is also somewhat reassuring, suggesting that while the other four may have been impressionable enough to go along with Mark’s plan, there isn’t a widespread trend of murderous teen delinquency afoot. The others will still have to take responsibility for their role in Mr. Griffith’s death and its subsequent cover up, but it looks like David, Jeff, and Betsy may face second-degree murder charges, and due to her limited involvement and willingness to testify against the others, Susan may only face a manslaughter charge. They made a terrible mistake, to be sure, but when it comes down to it, Mark is clearly depicted as the bad guy, allowing for a shift back toward the status quo for the other teen characters.

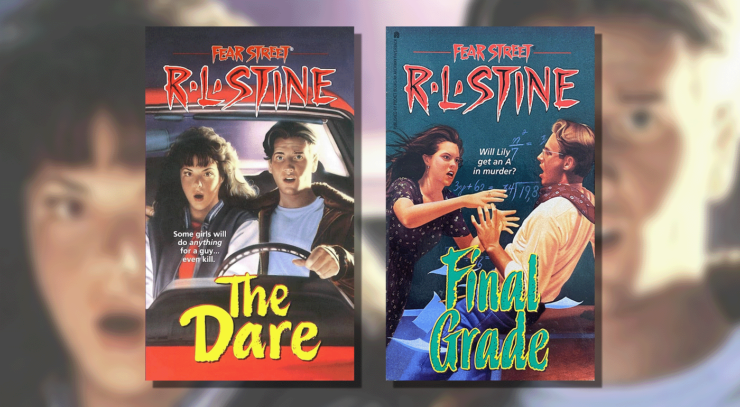

Stine’s The Dare and Final Grade build on the narrative pattern established by Duncan’s Killing Mr. Griffin: a teacher causes problems by refusing to cut them a little slack, or by holding them to a high standard, and the logical conclusion—at least to these teens’ minds—is murder. Socioeconomic disparity plays a central role in both books. In The Dare, Dennis Arthur and his friends are rich and popular, and used to getting what they want. The only person who won’t get with the program is Mr. Northwood, who teaches history at Shadyside High School, and has an idiosyncratic habit of recording all of his class lectures. Mr. Northwood won’t let Dennis take a makeup exam to accommodate his family’s annual trip to the Bahamas, which could cost Dennis his track team eligibility and the shot at an Olympic tryout. The issue of privilege is flipped in Final Grade, where Lily Bancroft’s family has limited resources and she will do whatever it takes to stay at the head of the class, be valedictorian, and get the scholarship that will change her life. The stakes are high in both cases, but that doesn’t mean everyone stands to suffer the same losses, and much like Mark’s manipulation in Killing Mr. Griffin, someone’s always pulling the strings to try to get away with murder, even if others take the fall.

In The Dare, Johanna Wise is excited for the opportunity to be part of the popular crowd, who suddenly want to be her best friends when they find out she lives next door to Mr. Northwood. Dennis starts taking Johanna out on dates (despite the fact that he already has a rich, popular girlfriend, Caitlin Munroe). Dennis, Caitlin, and their friends Melody Dawson, Lanny Barnes, and Zack Hamilton start hanging out at Johanna’s house on Fear Street, which is a far cry from their swankier homes in the North Hills neighborhood. The members of this friend group are always daring one another to do wild things, then throwing money or parental influence at any problem that the dares end up causing, from a Slurpy fight at the local convenience store to vandalizing Mr. Northwood’s car. When they start including Johanna in their dares, she figures they have really accepted her as one of their own, even if her dare is to kill Mr. Northwood.

Dennis and his friends appear to have zero conscience at all and face almost zero consequences for their actions. When they find a gun at Johanna’s house that she and her mom have for home protection, start playing around with it, and accidentally shoot Zack in the shoulder, they call the police, drag Zack into Mr. Northwood’s front yard, drop the gun on his doorstep, and tell the police “Northwood shot Zack!” (100). Northwood hears the ruckus, opens his door, and picks up the gun, which means he’s holding it when the police show up, but Dennis’s machinations are too clumsy to hold up to any scrutiny and the truth is soon discovered. While this could—and should—land them in a heap of trouble, their parents quickly pay off whoever they need to and hush the whole thing up. This seeming immunity is part of what Johanna finds alluring about Dennis and she thinks “I wondered what it would be like to be like Dennis, to feel like you can get whatever you want. That you can do anything—and get away with it” (104, emphasis original).

Johanna takes the dare to kill Mr. Northwood in part because she wants to explore this feeling further, to see what it’s like to not have to worry about the consequences of her actions, but she fails to realize that she doesn’t have the same privilege Dennis and his friends do. Dennis and the others start telling people at school about Johanna’s dare, taking bets on whether or not she’ll go through with it, and lining up plenty of corroboration that will implicate her when Mr. Northwood turns up dead. Dennis comes over on the day Johanna is set to kill their teacher to offer encouragement, though in the end she finds she can’t go through with it … but by then, it’s too late because while she was in the bathroom, Dennis went next door and shot Mr. Northwood, with all the evidence pointing to Johanna as the killer. Caitlin shows up to celebrate with Dennis and when Johanna asks him “You went out with me just because you wanted me to kill Mr. Northwood?”, Dennis responds with “Pretty much. It was a dare, see” (142). It’s kind of like Pretty in Pink (1986), but with murder instead of the prom.

The cops show up and find Johanna holding the gun (in an echo of their hackneyed framing of Northwood himself), Caitlin and Dennis tell the police that they tried to stop her, and there are a whole lot of people from school who will tell them that everyone knew Johanna planned to kill Mr. Northwood. The deck is stacked against Johanna, with Dennis and Caitlin’s privilege giving them an additional upper hand, and things look pretty grim. The only thing that averts a truly tragic ending for Johanna is that just like he records his lectures at school, Mr. Northwood frequently records himself as he talks through ideas on his own at home, and had a recorder in his pocket that caught it all, including Dennis and Caitlin’s confession. And unlike Mr. Griffin, Mr. Northwood is badly injured but not actually dead (at least in the book’s final chapters—it all seems a bit touch and go).

Just like everyone believes Johanna plans to murder Mr. Northwood, in Final Grade, when the social science teacher Mr. Reiner turns up dead, Shadyside high students immediately suspect Lily, who was upset about an exam grade she got in his class that knocked her into second place in the rankings for valedictorian. Like Duncan’s Mr. Griffin, Mr. Reiner sets a high bar for his students and when Lily asks him why she got a B on the exam, he tells her “there’s nothing wrong with your essay questions … And they’re good answers—B answers. But you didn’t bother to go the extra step. You didn’t write really excellent answers—the kind that deserve a top grade” (2, emphasis original). Lily pleads with him to change his mind and raise her grade, but Mr. Reiner is unmoved, and when Lily runs into her friend Julie Prince in the hallway after her conversation with the teacher, she tells her friend “I want to murder him” (7). Julie doesn’t think jokes about murder are very funny though, particularly since her brother was killed in a grocery store hold up a few years earlier. This is a horror that seems set to replay itself when a gunman comes in to rob the pharmacy that Lily’s Uncle Bob owns, and where she works part-time, but between the gun Lily’s uncle keeps in the drawer under the register and Rick Campbell, the slightly creepy but intrepid delivery boy Bob recently hired, no one gets hurt this time.

But of course it’s Fear Street, so it’s really only a matter of time. When Lily goes to talk to Mr. Reiner one more time, to inquire about an extra project she could complete to bring her grade up, she finds him dead on his classroom floor. All signs seem to point to an unfortunate accident—there was trouble with one of the lights and he climbed up on a ladder to try to fix it—but everyone is quick to believe that Lily killed him and “Whenever Lily raised her eyes, she saw people staring at her with accusing eyes—as if she had something to do with Mr. Reiner’s accident” (40, emphasis original). While Lily is innocent, this suspicion only deepens when Graham Prince—Julie’s cousin and Lily’s main competition for the valedictorian spot—turns up dead, killed in what looks like an accident at his family’s printing press, where a group of students were going to print the high school’s literary magazine. There is long-standing tension between Lily and Graham, who have been competitors throughout their entire school careers, and unlike Lily, who is relying on the scholarship that comes with being valedictorian to go to college and start a new life beyond Shadyside, Graham’s family is wealthy and he can choose his own post-graduation path, with or without the scholarship. Lily didn’t kill Graham either, but she’s realistic enough to realize that if someone casts suspicion on her for their murders, “Being innocent doesn’t matter … People will believe … People want to believe that you killed Mr. Reiner and Graham” (92, emphasis original).

And that’s exactly the leverage that one of Lily’s classmates, Scott Morris, intends to use against her. Scott and Lily work together on the literary magazine and Scott has been interested in Lily for years, though she doesn’t have any romantic feelings for him. Where Dennis dated Johanna in The Dare to draw her into his murder plot, Scott has the opposite plan: he has constructed a murder plot that will make Lily look guilty in order to blackmail Lily into going out with him. When she threatens to go to the police and tell them everything, Scott doubles down, telling her that if she does, he’ll tell them that she was in on the murders as well and he killed Mr. Reiner and Graham for her, so that she could be valedictorian. Since everyone seems a bit suspicious of her already, it doesn’t feel like Scott will have to do much convincing, and Lily reluctantly goes along with his plan, which quickly gets exploitative and icky, with Scott demanding she make out with him and proudly telling everyone he’s her new boyfriend (including Alex, who is actually Lily’s boyfriend, and doesn’t take this news well).

A domino effect of planned murders quickly begins to line up: Lily wonders if killing Scott might be the only way to end this horrible situation, while Scott finds out that Julie suspects him and plans to kill her too. Scott has Lily ask Julie to meet them at the printing press, which will give him the chance to kill Julie while also making Lily complicit, if not actually an accessory to the murder. Scott takes the gun from the drawer under the pharmacy register, shoots Julie, and is preparing to kill Lily too when she refuses to do as he says, when Julie seems to rise from the dead and clobbers Scott with a heavy metal bar. Julie’s survival remains a mystery until Uncle Bob shows up, relieved that they’re both okay, and tells them the gun he keeps in the pharmacy is a starter pistol, saying “I wouldn’t keep a real gun around. Too scary” (147). While a starter pistol may be of somewhat limited use if the robber hadn’t been scared off, it saved Julie and Lily, and they live to fight another day, with Lily’s obsession with being valedictorian undimmed, as she tells her friend in the book’s final lines “I’m going to finish first, Julie. I know I am!” (148, emphasis original). So murder and trauma aside, at least her academic priorities are still firmly in place.

These students are frustrated with their teachers for different reasons: in Final Grade, Lily is stressed about her grade and the possibility of being valedictorian (and the accompanying scholarship) slipping beyond her reach. In The Dare, it’s the athletic possibility of the track team and a potential Olympic tryout that drives Dennis, along with just not being able to handle being denied what he wants when he wants it. In Duncan’s Killing Mr. Griffin, the crux of the matter seems to be that Mark just doesn’t like Mr. Griffin, and he still feels angry about being caught cheating, which is enough to set the whole scheme into motion. In each of these cases, there are tangled webs of manipulation, exploitation, and blackmail that blur the lines between perception and reality, complicity and responsibility, tragic accident and premeditated murder.

At the heart of each of these horrors is a deep-seated fear of the violence that teens are capable of, though in each book’s conclusion, Duncan and Stine reestablish a (somewhat shaky) equilibrium. By isolating the central responsibility onto a manipulative ringleader—with Mark, Dennis, and Scott—readers are reassured that while there are a handful unstable and violent teens out there and a few others who may make bad choices that occasionally end in tragedy, they aren’t all heartless murderers.